I started a podcast!

Introducing Urban Affairs.

After many years of procrastination, I've finally started a podcast! Urban Affairs is my attempt to have interesting conversations about public policy in cities with all kinds of different people. Unlike this newsletter, it will not be focused exclusively on Austin, but naturally this city will play an outsized role.

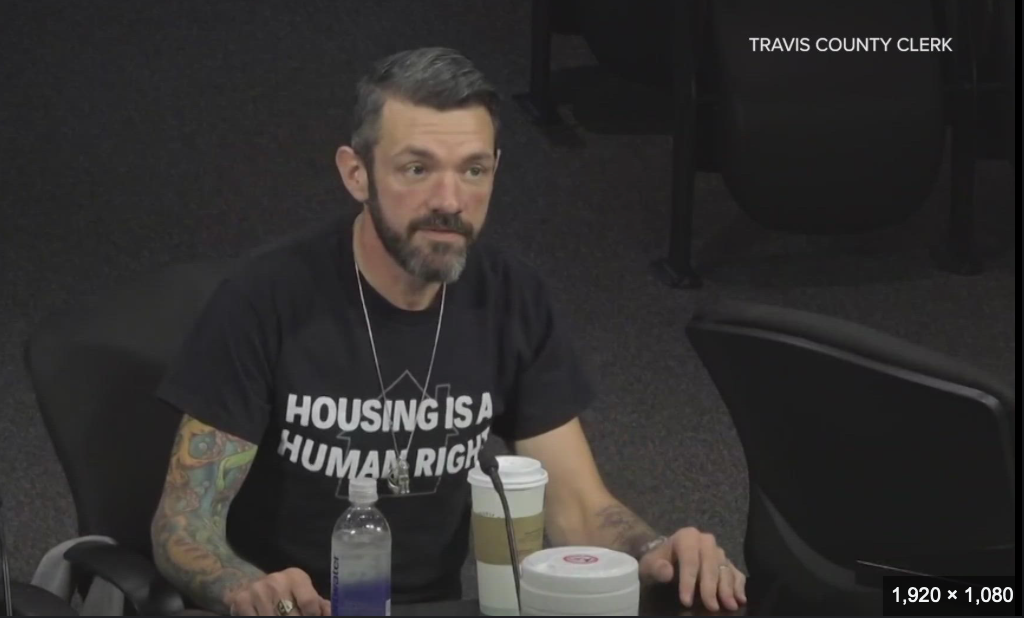

For my inaugural episode I invited Chris Baker, the no-nonsense executive director of The Other Ones Foundation, to talk about the state of homelessness in Austin and America. We talked about a wide range of big societal issues that have shaped this national tragedy: poverty, addiction, mental illness, the end of federal public housing, the deinstitutionalization of mental health care, a broken foster care system, exclusionary zoning, nonsensical federal housing regulations, and much more. We discuss how honest conversations about homelessness and evidence-based solutions are impeded by political ideology and virtue signaling on both the left and right. Last but not least, Baker offered some insights into his experience on Bravo's Queer Eye a few years ago.

It's a very long conversation but I think a very informative one, and even if you only listen to a portion of it, I think you'll learn something new.

You can listen through Spotify and it's also available on Apple Music. Please "follow" Urban Affairs on either on those platforms and, if you are so inclined, give it a good rating!

I'm still figuring this stuff out. There is still a lot of room for improvement on editing. Bear with me. And feel free to send me tips on how I can improve the product, including by recommending guests!

If you don't have time to listen, below is a heavily abbreviated and edited transcript, broken into a few different chapters.

Throw the Point In Time count "out the fucking window"

Me: Over the last four years, according to the Point In Time count, the Austin homeless population has more than doubled from just over 3,000 to just over 6,000. And that comes in the context of a nationwide increase of 18% to about 770,000 people, according to the national Point In Time count. Those 770,000 people, not are their lives miserable, but their misery has a profound impact on the day-to-day life. .

Baker: So from a political perspective at the city of Austin, it's certainly a thing we talk about a lot. It's one of the top five priorities of the city, but that is absolutely not reflected in the city budget. The roughly $80 million that the city puts into homelessness is a drop in the bucket compared to what we actually need our city to be investing.

And speaking of those numbers you cited from the Point In Time Count ... The Texas State Affairs Committee just put out a report on homelessness and I'm gonna read you my favorite passage from it: "Philip Mangano, the former head of the US Interagency Council on Homelessness has criticized PIT counts as 'one of the most unscientific activities that determines policy ever devised by the federal government.'"

So I'm a very, very strong believer you gotta take that number and throw it out the fucking window because it doesn't actually mean anything.

Me: So how does the PIT count work?

Baker: You take a single point in time and you send a bunch of people out into the community, a bunch of volunteers, and they literally just go out and count survey all the people that they can find who are experiencing homelessness. You have three hours to go out and count all the people.

The last time I did it I was given a section of South Austin. And the year before they had counted about 10 people in that area. But I went out the week before the count and I found where all the different encampments were and I built a route for us to go on the actual day. Not only did the count in that area increase from 10 people to like 60 people, but I only got about halfway through the route that I had built before the office called me and said it's time to get come back.

I think this is a thing that people do with the best intentions. It's not to throw shade on anybody.

Me: So you're saying it's a dramatic undercount?

Baker: It's a dramatic undercount and it's a very sort of performative exercise.

The invention of modern homelessness

Baker: Homelessness as it exists today, that's not really a thing that we've had for very long. I mean, the word "homelessness" was not even really a part of the popular lexicon until the 1980s.

Me: What changed?

Baker: I think there are two major contributing factors: the deinstitutionalization of mental health care and the disinvestment in public housing.

Me: So if homelessness as we think of it now is only 40 years old, why have we seen such a big rise in homelessness in the last decade? The problem has become much more severe.

Baker: Wages for people at the lowest end of the earning spectrum have stagnated and the cost of housing has skyrocketed to the point that it's unattainable to a lot of people. In Austin, to have an apartment and live comfortably, you gotta be earning at least like $90,000 if you're single.

What about drugs?

Me: If you look at people living under the highway overpass, it's hard to imagine them paying any level of rent due to mental illness, substance abuse etc.

Baker: Right. And there are some people for whom the conventional existence of having a job and paying for housing is just not in the cards.

Me: Why not?

Baker: A lot of reasons. Could be substance use disorder. Could be any myriad of mental health issues. It could just be disabling conditions.

Me: You've had your own addiction journey that I learned about watching you on Queer Eye. So talk to me about that.

Baker: Well, I've lived with substance use disorder my whole life, you know.

I'm happy to say that I've been in a period of abstinence for some years now. And I'll tell you the thing about addiction from my experience that is kind of bewildering. You don't mean to do it. And it's a really difficult experience to explain to people who haven't been there. But it's almost as if this outside entity comes and takes over your body and brings you to a dope man or brings you to a liquor store.

Me: The last time we talked you described the height of your drinking problem. The amount you were able to drink blows my mind.

Baker: When I was at the end of my rope with drinking, it was just a hassle. There was no more fun in it. And my process was, I would wake up in the morning, I would buy two 12 packs of vodka single shots, right? And that would be followed by a 12-pack of beer. And then on the drive home from work, it's like a few tall boys, right? And so we're talking about 40-plus drinks a day every day.

Me: Before I talked to you I would have thought that that level of drinking would necessarily mean you're living in the gutter. I don't understand how you were drinking that much while also being the functioning head of a nonprofit.

Baker: It was before we were a big company and I certainly couldn't do my job now and be doing that level of drinking, but it's bizarre how when you wake up in the morning and you have vodka with your coffee, you're kind of just like drinking all day. It's like you never really get drunk. You know? You wake up and you've got shakes and you gotta deal with those shakes. And you just drink.

Me: So I guess this gets to a big question in the homelessness debate is to what extent is our homelessness crisis driven by substance use?

Baker: That's a good question. My experience is that most of the people that we're serving have some kind of unhealthy relationship with substances. And when I say most, you know, call it 60%, right? Not the overwhelming majority.

There is like a chicken and egg thing to it. Are people falling into the experience of homelessness because of their substance use disorder or are people picking up a substance use disorder because they fell into homelessness? And it's both.

Me: The same goes for mental illness, right?

Baker: Absolutely.

Me: I was talking a couple of years ago to someone who works in the homelessness nonprofit space in Austin. And I was just interested in asking him about the opioid epidemic how it was driving this increase in homelessness. And this person I was talking to was just so hostile to that line of questioning. I remember him telling me, "Nobody has ever become homeless because of drug addiction."

Baker: Haha! Well that's just false on its face.

The Almighty support network

Baker: I like to think of it like a superhighway with different exits that lead into homelessness.

So a shockingly high amount of the people that we serve have aged out of the foster care system. So that support network was just never there to begin with.

At The Other One's Foundation, what I always tell people is that the primary reason we exist is to build a support network around people who, for whatever reason, have lost their support network elsewhere.

And ultimately, I'm of the belief that that's what Homeless Response is all about. We rebuild support networks for people.

The rent is too damn high

Me: And let's talk about the other thing that progressives are much more comfortable talking about: the rent is too damn high.

Baker: Yeah. Until the 1980s, we had a lot of options for public housing. And that's just not the world that we're living in now.

And now, even as homeless advocates, we just accept that public housing is not a part of the conversation. And we work towards creating housing interventions like permanent supportive housing, which is very, very expensive. It's not scalable.

Don't get me wrong, old school public housing projects got a bad rap for a reason. But right now our community is working on bringing something like 400 units of permanent supportive housing online. And that's just nowhere near enough to tackle the problem.

Me: So are there ways to serve people less expensively than PSH?

Baker: You've got a really good example of something that's not actually PSH that functions way better and has way better outcomes: Community First Village.

But Community First Village is not eligible for many government subsidies because of federal housing quality standards that require each unit to be at least 225 square feet, have its own bathroom, have its own sink outside of the bathroom, has to have a way to prepare food, etc.

But people do really, really well at Community First Village. They get a little cottage. It doesn't have a bathroom inside, but there's one within walking distance. It's 300 bucks a month. Somebody living on disability can afford that.

Me: What do you think about the zoning reforms City Council has pursued. These reforms are largely aimed at creating more market rate housing. Do you see that is having an effect on your work?

Baker: 100%, without question. Again, the sort of patterns of homelessness do kind of follow the housing market.

I think the real fight to end the housing crisis is playing out in front of local zoning and planning commissions.

Embrace unconventional housing, unconventional work

Me: So, tell me about Camp Esperanza. Who are the people you serve and how do you serve them?

Baker: We serve mostly chronically homeless, single adults, and our facility is what they call a non-congregate shelter, meaning that everyone that winds up staying there has their own space. They have a door that locks behind them. Our cabins are about 100 square feet, so we're not talking about the Ritz-Carlton. You have shared bathrooms.

We give someone a place to live. And while they're under our care, we work on a whole host of issues that are aimed at either getting somebody into the right housing situation permanently or getting them on the road to self-sufficiency.

So we recently built a vocational training school right on the campus. We give folks the opportunity to skill up and work with them on finding a job, keeping a job, and then we shift our case management focus to employment stability, and then housing stability follows that.

That's not to say that we compel every person that comes through our door to go and receive vocational services, because for some people, that's just not the answer.

Me: So of the people you're serving, what percentage do you think could go on to live an independent life with a job and conventional housing on their own?

Baker: I think 60-70 % of people can get there. Some people need a lot of help to get there.

The Other Ones Foundation started as a work program, Workforce First. You don't need to have an ID, you don't need to have a social security card, you don't need to have any job experience. We'll get you on a work van, we'll get you out into the community to do some work.

And what's amazing is the way in which people absolutely flourish. People will come into that program often thinking this is just an alternative to going out and panhandling. But then they start using the program to its full capability, and they're finding part-time jobs and they're getting their driver's license back for the first time in 15 years etc.

None of them are really incapable of working in our program because it's only a few hours a day. But I would say that close to zero of those people would be successful walking into a nine to five job in the same way that they're successful when they come into our program.

What the right and left can agree on

Me: So if you estimate that 60% of the people you're dealing with can get to a place of relative independence and stability, that still leaves a big chunk of people who you don't think can realistically attain that. And do we just gotta suck it up and pay for these people to?

Baker: At the end of the day, yes, that's it. It's always gonna be cheaper to have somebody in a housing unit than it is gonna be to have somebody on the streets for the taxpayer.

Me: Right. Even if I weren't a bleeding heart liberal and didn't have an ounce of compassion for the people camping by my kid's school, I would rather pay to house them –– out of selfishness! Because that would improve my quality of life.

Baker: I agree with you 100%. The idea that somebody has to share our intentions in order to want the same outcomes is fucking bullshit. The governor did not want people living under overpasses. And Mayor Steve Adler did not want people living under overpasses. But they're fighting about it. Why? We both want the same thing.

There's a really strong desire to fix these systems on the part of Republicans and Democrats and independents. And I just can't stress enough, I used to call it the "come on wit it" approach. If you want public safety, come on wit it. You've got a bleeding heart and you don't want to see people suffering, come on wit it. You want to be able to bring your kids to the park and you are sick of seeing people doing things in public that most of us do in our homes because we have them, come on wit it. If we're working together we're going to go a lot further.

Me: What were your thoughts on the decriminalization of camping that took place in 2019 and then the backlash that recriminalized camping?

Baker: I thought when they decriminalized camping that it would very likely lead to better outcomes for homeless response agencies. But I think it led to such disruption of public life for people that it wound up being a net negative for our cause.

But you know on the other hand I think there's also an argument to be made that our community needed to see that.

But it's a tough issue. At the end of the day, what good is it gonna do to give somebody a ticket? They're not gonna be able to pay the ticket.

And so the question ultimately is, what does enforcement look like? And I think that our city has come up with a pretty good way, which is that they do limited enforcement, and when they do the enforcement, they, to whatever extent is possible, try to offer everybody another place to go. Usually shelter beds.

But the shelter system is maxed out most of the time. And so there's this delicate dance of enforcing once there are open beds.

And the camping ban, in and of itself, is not a solution to anything other than now people don't have to see it.

Me: How would you judge the city's response to homelessness? Great or greatest?

Baker: Not great, not greatest, but good. And I think there's a lot of stuff that's outside of the city's control that impacts their ability to serve people in a way that would make them great or greatest.

I think that we really over invested in rapid rehousing to much the detriment of a lot of people. We are seeing massive amounts of people whose rapid plans are expiring heading back to the streets now.

Me: So Rapid Rehousing means just putting somebody in a market rate apartment unit, paying their rent for a year or two. And what you're saying is a lot of people who need much more intensive help than that are getting in an apartment unit, but there's no plan in place to set them up for success after that subsidy expires.

Baker: That's right. We're seeing a lot of people falling back into homelessness.

We have a homeless strategy officer at the city of Austin named David Gray now who's really good, really good, and if we are going to get to be a great homeless response system, I think he's the guy to get us there.

The contracting process for social service agencies is very, complicated. The barrier to entry is very, very high.

Me: What do you think about the city converting hotels into shelters or permanent supportive housing?

Baker: I have no qualms with the city buying hotels. I think it's a smart use of money.

But the overall health of our homeless response system is driven by so many factors? And so you get people into a hotel or a shelter and there has to be a pathway to get them out so that we can open up a new bed for someone else to come in.

Me: So if there are some existing federal regulations that you believe hamstring homeless response, do you think there's any chance the Trump administration might actually prove helpful on?

Baker: If something that we can pull out of this whole shitty mess is that we can do housing quality standard reform, I think that would be positive.

If somebody forwarded you this email, please consider subscribing to the newsletter by visiting the website.