Save Our Sprawl

Why don't 90's enviros get it?

During my past handful of evening walks around the neighborhood, I've been listening to KUT's new podcast series, Growth Machine, produced by KUT housing reporter Audrey McGlinchey. It's an excellent look at some of the big political, cultural and economic forces that shaped the Austin we know today: the 1928 master plan, the construction of I-35, and more recently, the Save Our Springs movement.

I especially appreciated the episode on Save Our Springs. The news clips from the early 90's offer a glimpse into a very different political atmosphere, characterized by conflict between a conservative and decidedly Texan business establishment and an insurgent group of young(er) liberal environmentalists who speak in quasi-religious terms about protecting Mother Nature from being plundered for profit.

Whatever I think of what has since become of the Save Our Springs Alliance (more on that later), I couldn't help but delight in their confrontations with an adversary, mining magnate Jim Bob Moffett, who, as KUT's Mose Buchele aptly put it, seemed like a "villain in a Muppet movie."

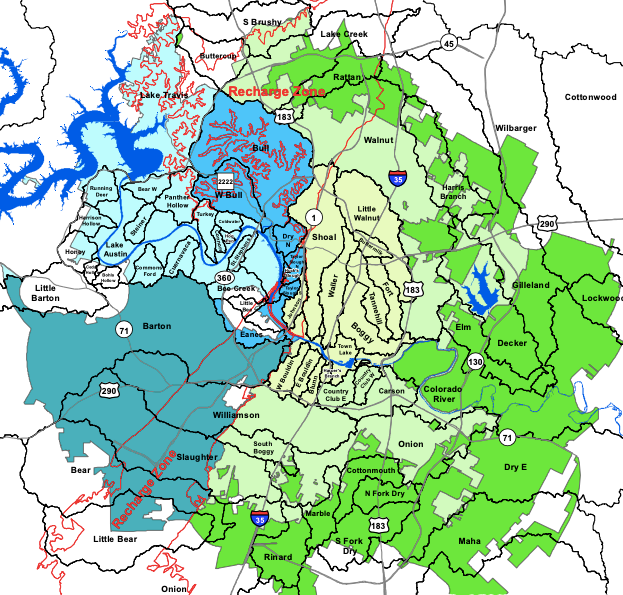

At the time, SOS was fighting the good fight against sprawl. The resulting political compromise recognized at least a theoretical distinction between healthy, environmentally friendly urban growth and unhealthy suburban sprawl. Hence the division of Austin into two distinct land use designations: the Drinking Water Protection Zone and the Desired Development Zone.

A subsequent episode of Growth Machine describes this compromise, forged in the late 90's by then-Mayor Kirk Watson, as part of a move towards "smart growth." To arrest sprawl threatening the aquifer, the city would encourage businesses (and even residents!) to locate downtown.

In reality, Austin never really embraced smart growth. Downtown and West Campus greatly densified, but the great majority of the region's growth continued to occur via sprawl on the outskirts of the city and in neighboring suburbs. The SOS restrictions in southwest Austin definitely increased development pressures everywhere else in the city, including East Austin, but contrary to what some activists and academics in Growth Machine claim, "smart growth" isn't responsible for gentrification on the east side. Nearly all of the land on the east side that was zoned single-family 30 years ago is still zoned single-family. The lots have just become much more expensive, predictably leading to displacement.

It's just now –– in the past six months, really –– that Austin has begun to take serious steps towards smart growth. Affordability, rather than the environment, is the main rallying cry for the measures Council has passed to rein in compatibility regulations, eliminate parking requirements and reduce minimum lot sizes, but these are absolutely the types of policies that will reduce sprawl.

So why then, are the original anti-sprawl warriors against all of this?

A Bunch of contradictions

In an email to supporters last week, Bill Bunch, a founder of the SOS movement and longtime executive director of the Save Our Springs Alliance, denounced the proposal to reduce minimum lot sizes as an "attack on our shared future." If you've followed Bunch in recent years, this isn't surprising; he and other early 90's greens, including former SOS executive director Brigid Shea, are closely associated with the "neighborhood" movement. Bunch is on the board of Community Not Commodity, the anti-density group led by Fred Lewis that opposes even the mildest land use reforms.

I was somewhat surprised to see Bunch invoking climate change in his denunciation. That's so very 21st century of him. I'm often struck by how little he and many other 90's Austin enviros dwell on climate change, which didn't take off as the central environmental concern until the late 90's/early 2000's. They're silent on the I-35 expansion. Their support for Project Connect was lukewarm at best (SOS didn't take a position). And of course, they vehemently oppose land use policies that will allow Austin to grow into a denser, less car-centric city. By blocking infill development in the city, they have helped facilitate sprawl.

The other day I sent Bunch an email asking him to explain why he would oppose policies that will allow the city to become more compact. He didn't initially reply, but when I prodded him again this morning he responded with characteristic acidity:

Given your pablum and utter lack of interest in the facts, why should I spend even a moment of my time addressing you?

I'll break my personal rule here and give you about 30 seconds.

We have supported densifying the central city along corridors, downtown, in growth nodes, all identified as places for increasing density in the Imagine Austin Comprehensive Plan. All this should and can be done while reducing impervious cover, not expanding it. The city wide attack on SF zoning will necessarily increase impervious cover tremendously, not decrease it, further destroying our tree canopy when we need to be protecting all of the trees we have and expanding our tree canopy. It's an attack on yards (aka greenspace) as much as it is on the families who own this housing, most of it located in working class neighborhoods and much of it bought back when homes were still affordable.

As he has done before when sending me testy emails, Bunch CCed a bunch of friends in politics and media. I don't know if the point is to intimidate me or if he just doesn't know how to BCC.

His point about impervious cover might be true on a given lot, but in the long-term increased density leads to less impervious cover. If you want less land to be paved, then you gotta build up! Nothing better demonstrates this than the Brodie Oaks PUD, a project that will transform an 80's-era shopping center into a dense, mixed-use development. The project will lead to a substantial decrease in impervious cover but is nevertheless vehemently opposed by SOS.

The contradiction arises from the fact that Bunch, like many other environmentalists in his generation, don't view "sustainable" growth as the key to environmental protection. Their preferred solution is no growth.

Hence Bunch's comments to Council last week, when he said that the issue with the housing market was not insufficient supply, but rather too much demand. In other words, too many people.

"We have a housing demand problem," he said. "The libertarian tech bros who want to blame the central city people, when they are causing the problem by stampeding the city with hyper-growth and super high-paying jobs, so that the market is dictating these sky-high prices on everything new that's built."

In a wide-ranging interview with the Texas Legacy Project five years ago, Bunch appeared to acknowledge a growing divide between himself and mainstream environmental organizations over growth, which he described as a "third rail" of U.S. politics.

I don't foresee Bunch ever conceding that allowing more people to live in Austin is an important part of making it a sustainable, climate-friendly city. But other environmentalists definitely get it. Among the groups endorsing Leslie Pool's minimum lot size reform were Environment Texas and –– the organization that will be key to reducing fossil fuel emissions –– Capital Metro. Yes, the more people we let live in central Austin, the more transit ridership grows. If we really care about the environment, that's the kind of growth we should all support.

Want more articles like this about city politics? Click "subscribe" and get the Austin Politics Newsletter in your inbox 4x a week!

There's the budget and the budget

It's that time of the year when I have to remind you that 75% of the city's $5.5 billion budget is made up of enterprise departments that are not funded by your taxes.

— Jack Craver (@JackCraver) July 27, 2023

If you wanna bitch about taxes, focus on that green slice, which is about $1.3B. pic.twitter.com/iLa7iPdl8w

I'll add that the Convention Center is also funded by taxes –– hotel taxes.