The billion dollar bike plan

$1 billion could give Austin a world-class pedestrian and bike system.

On Nov. 30, City Council is scheduled to vote on an update to the city's Bicycle Plan.

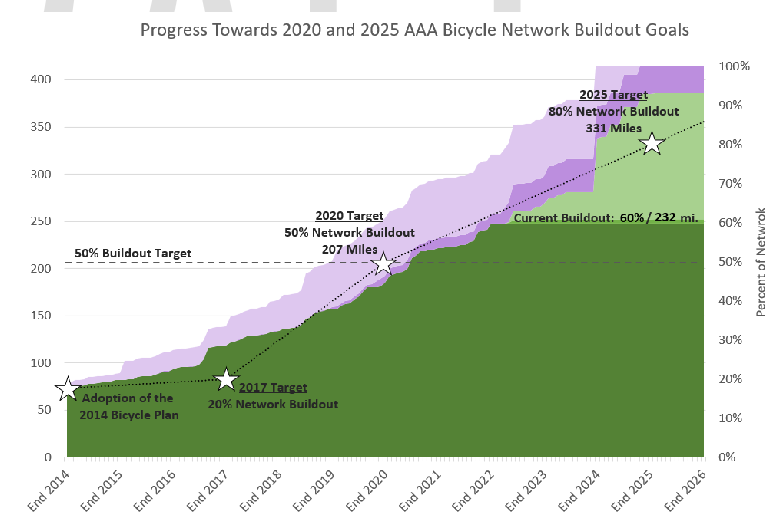

The Bicycle Plan was last adopted in 2014 and established the goal of creating an All Ages and Abilities bicycle network, which would in theory allow people age 8-80 to comfortably and safely get around on bike.

As part of the plan, the city conducted a survey of Austinites and found that while only 17% said they currently felt safe biking on city streets, 55-60% would feel safe if the city provided enough "protected bike lanes and urban trails."

A lot has changed since 2014. On the bright side, we now have a lot more bike infrastructure, both in the form of expanded urban trails and many more semi-protected bike lanes on streets. Furthermore, the advent of e-bikes has significantly increased the appeal of biking.

On the other hand, it's become clear that the authors of the 2014 plan greatly underestimated the cost of building a comprehensive bike network. It will take far more than the $151 million proposed in the 2014 plan to put in place a system that makes upwards of half of the population comfortable using bikes at least some of the time.

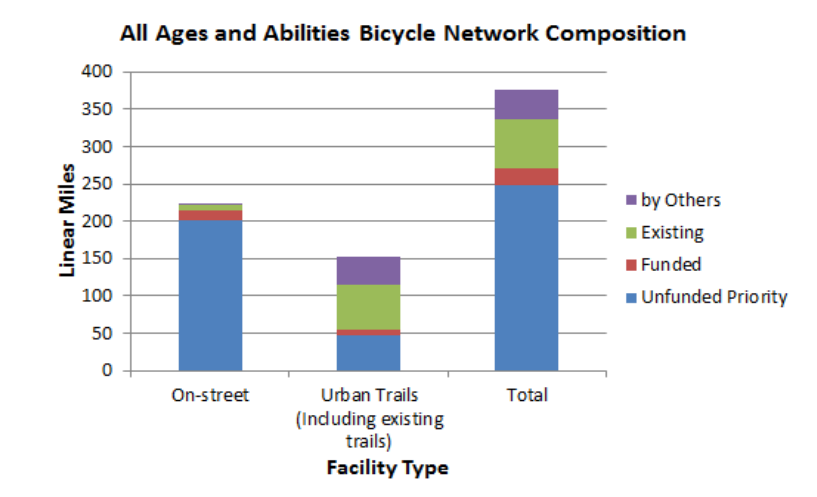

The network envisioned in 2014 consisted of 220 miles of on-street facilities and 150 miles of off-street trails, or 370 miles in total.

The proposed update celebrates the progress towards the goals established in 2014, claiming that the city had built 60%, or 232 miles, of the 370 mile goal by the end of last year.

But the update also dramatically expands the goals established a decade ago. The envisioned network now includes over 1,200 miles of bike lanes and shared use paths, including 800 miles that have yet to be built or funded.

And that doesn't even account for the 236 miles of urban trails identified in the recently-updated Urban Trails Plan.

A closer look at costs

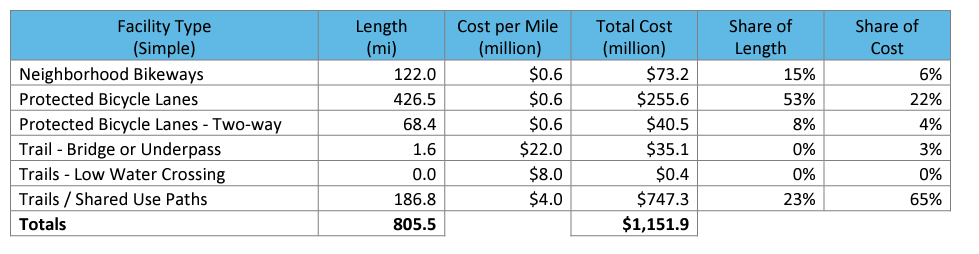

The total estimated cost of the additional 800 miles is $1.15 billion.

However, most of that is tied to "Trails/Shared Use Paths" which, according to city bike czar Nathan Wilkes, are mostly not expected to be funded or built by the city. Most of them are shared use paths (in some cases glorified sidewalks) that will be provided by TxDOT or CTRMA, the toll road authority, along their highways, or as parts of private developments. Whether this bike infrastructure will prove valuable is up for debate, but it's mostly not the city's responsibility.

If we subtract the SUPs from the equation, we're left with a cost of $404 million. That's 10x what was allocated to bikeways in the 2020 active mobility bond.

It's also important to remember that these cost estimates depend on a variety of assumptions. For instance, Wilkes told me recently that the per-mile cost for the lanes "protected" by white flex posts is only $50-100k, but that that increases to between $400k-$1M for concrete barriers.

But even $400 million won't be enough to achieve the truly transformative change that Austin deserves. Humanizing our streets with better sidewalks and bike lanes is crucial, but we also need a big investment in what are essentially pedestrian and bicycling highways: urban trails.

Not only are trails like the Butler Hike & Bike Trail and the Shoal Creek Trail crucial pieces of infrastructure, but they become beloved refuges for leisure and recreation and will be doggedly defended by their nearby residents and their elected officials.

The projected per-mile cost of urban trails in 2014 was $2 million, but the most recent Urban Trails plan update assumes a per-mile cost of $6 million. So that would assume a cost of over $500 million for just the 84 miles of Tier 1 urban trails and $1.4 billion for the full 236 miles.

Unfortunately, the most recent update to the Urban Trails Plan says even the city's top priority trails won't be built until 2043. That's unacceptable. Council members and advocates need to push for a more aggressive timeline, which no doubt demands more money, whether that is a bond next year or in 2026.

$400 million for bikeways + $500 million for Tier 1 urban trails puts us at $900 million. We should aim to have that built in the next decade. Interim City Manager Jesus Garza, who has said he doesn't want any bonds next year and is rumored to be skeptical of bike infrastructure, will probably try to stand in the way, but Council should just plow through him. He does not represent this city's future.

A billion is not too much to ask

Just to be clear: a billion bucks for a world-class bike network isn't a rip-off. It's a bargain.

One of the things that makes Austin special is the communal spaces where people can safely and enjoyably exist outdoors. Barton Springs & Zilker Park are community treasures; no wonder people are so sensitive about them. We must build upon this by not only creating more parks and other public spaces, but more livable, enjoyable streets and a system of trails that offer scenic ways to navigate the city by foot or bike. Don't we want that for our kids?

Pedestrian and bike infrastructure is a meaningful response to so many of the biggest challenges facing 21st century American cities: poverty, climate change and the physical and mental health problems linked to our increasingly sedentary lifestyles. That's not to say that other policies aren't necessary to handle those problems, but this one has the advantage of providing so many simultaneous benefits so cheaply. It's also not nearly as vulnerable to interference from the state or bored local attorneys.

So kudos to everyone involved in this plan, including city staff, for being frank with the city about what it would take to build a truly comprehensive bike network. The era of scraps for active transportation must end. The $460 million active mobility bond in 2020 was a good start, but we've got a lot more work to do than that.

Let's talk about goals

There are different reasons to support an All Ages and Abilities network.

There's a kind of moral/equity objective, in which low-cost mobility is a right to which everybody should have access. Through this lens, the top priority is to expand the coverage of the network, even if the infrastructure is not top-notch (flex posts). In this framework, it would be better to give everybody a C+ bike network than to give some people an A+ network and others an F network.

Another approach would be to focus on maximizing bike trips. Or perhaps maximizing the number of car trips replaced by bike trips. In this framework, it might make more sense to focus on building high-quality bike infrastructure that would make biking very popular in certain parts of town, even if it leaves certain parts of town as cycling deserts. "We'll get to them later."

For obvious reasons, I don't expect anybody to publicly embrace the latter approach. It's kind of a buzzkill politically.

My concern is that we're opting for the C+ network with the expectation of A+ (or at least A-) outcomes. Wilkes directed me to a 2015 study of bicyclists in a handful of cities, including Austin, that suggested that concrete barriers did not significantly increase the perceived safety of a bike lane over flex posts. I'm very skeptical that the survey, which relied on people rating different lanes based on illustrations, accurately reflects how people would react in the real world.

To be clear, I appreciate the installation of flex posts on bike lanes that were previously just painted lines, but I'm skeptical that they are enough to actually convince otherwise hesitant people to start biking. And I simply do not accept that many of these bike lanes can be classified as All Ages and Abilities –– I don't think even many free range parents would feel great about their 8-year-olds biking in the "protected" bike lane on S. Congress.

Part of the problem is that safety and comfort are difficult to forecast just based on the type of physical separation. The size of the bike lane also likely matters a great deal, as well as the speed of the passing cars and surroundings.

The road diet pilot on Barton Springs Rd. is an example of how to make biking much more comfortable on the cheap. The physical barriers are nothing special –– flex posts and little "armadillos" –– but there is a ton of space in between the bike lane and the car lane. Furthermore, because there is only one car lane left, cars are moving more slowly.

In contrast, the barrier on Slaughter Ln is more solid, but I doubt that most people would rate it as more comfortable. That's because Slaughter is still a pure-bred car sewer, with three lanes of extremely fast-moving cars on each side of the road.

The discomfort is not just tied to a perceived threat of serious injury or death. The same is true of walking. The reason you see so few people walking along most of our major corridors isn't because they're horribly dangerous. They're just unpleasant because they weren't built for pedestrians, but for cars.

Anyway, this all goes back to funding and political will. The only reason to skimp on bike infrastructure is because elected officials aren't willing to a) demand enough funding for it and b) aren't willing to take space away from cars.

We need better data

It's really important that the city start measuring the effect of new bike infrastructure. The city already has a bunch of counters that track the number of pedestrians and cyclists, but they're almost all on trails. We need to get a better sense of the cycling traffic in bike lanes, and we need to get a sense of before/after.

The Transportation & Public Works Dept tells me they are planning on installing a counter on the segment of Barton Springs Rd (between Lamar & Azie Morton) that is testing out reduced car lanes and an expanded bike lane. That's great, although it would have been nice to have collected some data on bike use before the changes were made too.

Stick to bikes

As is often the case in city plans, the proposed update includes a lot of well-intentioned but cringey social justice discourse.

For instance, it makes perfect sense to include a frank discussion of the forces that have shaped Austin and its transportation systems, which would naturally include segregation, racist highway planning and underinvestment in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods.

But instead we get an acknowledgement at the beginning with the familiar, quasi-religious "In this house we believe..." vibe. After providing a rundown of historic racial injustices (slavery, Jim Crow, redlining), it makes a number of very debatable assertions about gentrification and displacement that I imagine would draw objections from many of those who took part in crafting this plan.

For instance, it's certainly true that affluent neighborhoods have more aggressively and successfully fought new housing, but it is not quite right to say that the Save Our Springs ordinance "set East Austin as the Desired Development Zone in the name of protecting the aquifer recharge zone in affluent west Austin against the express wishes of East Austinites." In fact, the DDZ covers much more than East Austin and it's hardly true that East Austin residents were united in opposition to SOS.

Then there's this abrupt claim:

The real estate and redevelopment industries continue to actively support segregation and displacement because predominantly white communities are perceived as higher value.

There definitely is a long history of racism in real estate, and it certainly persists in various forms, but the gentrification in Austin occurring now has much more to do with predictable market forces. The real estate industry is mostly just following the market. Anyway...it's not really a debate that needs to occur as part of a bike plan.

Finally, there's a semi-apology for taking inspiration on bike infrastructure from the Dutch because of their role in the international slave trade in the 18th century:

Why didn't the plan acknowledge that the first bicycle was invented by Karl von Drais, a German baron who likely would not have had the time and resources to invent a new form of mobility if not for his place atop an oppressive caste system?

The irony is that elsewhere in the plan the authors concede that their public engagement efforts failed to generate as much participation from marginalized communities as hoped. Ya think? It would never occur to people with actual problems to worry about whether multi-modal infrastructure is somehow linked to Dutch imperialism.

Seriously, are y'all trying to get featured in a Ron DeSantis campaign ad? Fortunately I don't imagine too many GOP legislators are going to get offended on behalf of the Dutch, but dear God, this is the kind of woke nonsense that the right feasts on.

Come on people. This is not a graduate seminar at Oberlin. This is the real world, inhabited by real people with real problems. If you want to help them, speak to them in a language they understand.

I do not doubt the sincerity of the city's transportation planners in wishing to build infrastructure that advances economic and racial justice. The best way for them to do that is to stick to bikes.

If you were forwarded this newsletter, please consider signing up to receive it daily.